Wednesday, January 7, 2015

Quote #159: on the lack of priestly vocations

“If we are not training young men as altar boys, giving them an experience of serving God in the liturgy, we should not be surprised that vocations have fallen dramatically." - Raymond Cardinal Burke.

Tuesday, January 6, 2015

Quote #158: God's presence

"God is in all things." - St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicae, I, 8, 1.

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

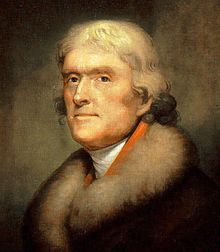

Quote #157: Jefferson on the nature of freedom of religion

Well aware that the opinions and belief of men depend not on their own will, but follow involuntarily the evidence proposed to their minds; that Almighty God hath created the mind free, and manifested his supreme will that free it shall remain by making it altogether insusceptible of restraint; that all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments, or burthens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and are a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, who being lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was in his Almighty power to do, but to extend it by its influence on reason alone[.]-- The Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786).

Saturday, February 22, 2014

Quote #156: Thomas Jefferson on federalism and the free exercise of religion

"In matters of religion, I have considered that its free exercise is placed by the constitution independent of the powers of the general government. I have therefore undertaken, on no occasion, to prescribe the religious exercises suited to it; but have left them, as the constitution found them, under the direction and discipline of state or church authorities acknowledged by the several religious societies."

- Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1805.

- Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1805.

Labels:

freedom,

god in america,

god in society,

good government,

liberty,

presidents,

religion

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

Quote #155: on the danger of big government

"Remember that a government big enough to give you everything you want is also big enough to take away everything you have." -- Barry Goldwater (1909-1998).

Sunday, December 9, 2012

Quote #154: The Purpose of Advent

"Advent is concerned with that very connection between memory and hope which is so necessary to man. Advent’s intention is to awaken the most profound and basic emotional memory within us, namely, the memory of the God who became a child. This is a healing memory; it brings hope. The purpose of the Church’s year is continually to rehearse her great history of memories, to awaken the heart’s memory so that it can discern the star of hope."

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI).

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

Quote #153: those who fight the Church

"Men who begin to fight the Church for the sake of freedom and humanity end by flinging away freedom and humanity if only they may fight the Church."

- G.K. Chesterton.

- G.K. Chesterton.

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

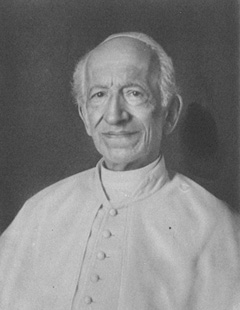

Quote #152: the Catholic idea of government emphasizes substance over form

Some more worthwhile perspective from Pope Leo XIII:

There is no question here respecting forms of government, for there is no reason why the Church should not approve of the chief power being held by one man or by more, provided only it be just, and that it tend to the common advantage. Wherefore, so long as justice be respected, the people are not hindered from choosing for themselves that form of government which suits best either their own disposition, or the institutions and customs of their ancestors.

But as regards political power, the Church rightly teaches that it comes from God, for it finds this clearly testified in the Sacred Scriptures and in the monuments of antiquity; besides, no other doctrine can be conceived which is more agreeable to reason or more in accord with the safety of both princes and peoples.- Diuturnum (On Civil Government), paragraphs 7 & 8 (1881).

Monday, June 4, 2012

Quote #151: man as a social animal

"And indeed nature, or rather God Who is the author of nature, wills that man should live in a civil society; and this clearly shown both by the faculty of language, the greatest medium of intercourse, and by numerous innate desires of the mind, and the many necessary things, and things of great importance, which men isolated cannot procure, but which they can procure when joined and associated with others."

- Pope Leo XIII, Diuturnum (On Civil Government) (1881).

- Pope Leo XIII, Diuturnum (On Civil Government) (1881).

Labels:

conservatism,

god in society,

human nature,

religion,

social reform,

theology

Quote #150: American or English?

"America has a right to a language of its own, and to the largest share in forming that pigeon-English which is to be the 'world-language' of the future."

- George Santayana, America's Young Radicals (1922).

- George Santayana, America's Young Radicals (1922).

Saturday, January 7, 2012

Quote #149: on the value of the study of history

"The study of history is a powerful antidote to contemporary arrogance. It is humbling to discover how many of our glib assumptions, which seem to us novel and plausible, have been tested before, not once but many times and in innumerable guises; and discovered to be, at great human cost, wholly false."

- Paul Johnson, The Quotable Paul Johnson: A Topical Compilation of His Wit, Wisdom and Satire, edited by George J. Marlin, et al (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994), p. 138.

- Paul Johnson, The Quotable Paul Johnson: A Topical Compilation of His Wit, Wisdom and Satire, edited by George J. Marlin, et al (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994), p. 138.

Thursday, January 5, 2012

Quote #148: the benefits of a good wife

Happy is the husband of a good wife; the number of his days will be doubled. A loyal wife rejoices her husband, and he will complete his years in peace. A good wife is a great blessing; she will be granted among the blessings of the man who fears the Lord. Whether rich or poor, his heart is glad, and at all times his face is cheerful.- Sirach 26:1-4 (Revised Standard Version, Second Catholic Edition).

Labels:

Bible,

ethics,

family,

morality in society,

theology

Quote #147: Jefferson on the Enlightenment

[O]n the eighteen century. It certainly witnessed the sciences and arts, manners and morals, advanced to a higher degree than the world had ever before seen. And might we not go back to the ear of the Borgias, by which time the barbarous ages had reduced national morality to its lowest point of depravity, and observe that the arts and sciences, rising from that point, advanced gradually through all the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteen centuries, softening and correcting the manners and morals of man? I think, too, we may add to the great honor for science and the arts, that their natural effect is, by illuminating public opinion, to erect it into a sensor, before which the most exalted tremble for their future, as well as present fame.- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to John Adams dated January 11, 1816, taken from In God We Trust: The Religious Beliefs and Ideas of the American Founding Fathers, ed. by Norman Cousins (Harper & Bros.: 1958), pg. 266.

Tuesday, January 3, 2012

Quote #146: true and false equality

"The only true forms of equality are equality at the Last Judgment and equality before a just court of law; all other attempts at levelling must lead, at best, to social stagnation."

- Russell Kirk (1918-1994), American writer and conservative theorist.

- Russell Kirk (1918-1994), American writer and conservative theorist.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Quote #145: on block quotation

Probably not a suitable quote for this blog, but worth reading if one plans on doing any original writing:

I assure our readers that the quotes posted on this blog serve not as substittues for, but rather encouragements to, rigorous thinking.

It is a good idea to avoid long quotations, especially quotations long enough to require indentation. Tehe are few such quotations in academic writing that could not better be paraphrased. Long quotations not only discourage the reader, they often serve as a substitute for thought on the part of the writer.- Christopher Lasch (1932-1934), Plain Style: A Guide to Written English (University of Pennsylvania Press: 2002), pg. 65.

I assure our readers that the quotes posted on this blog serve not as substittues for, but rather encouragements to, rigorous thinking.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Quote #144: Archbishop Oscar Romero on hope

The words of a great martyr for the faith and

for his people who spoke about hope in the

face of what appears to be insurmountable

problems:

"Hope is not resignation; it is a commitment

to continue to struggle even when things seem

to warrant surrender, when hope flares, it

allows human beings to overcome monstrous

difficulties. It allows people to defy common

sense and confound strategists. Hope

experienced in the extreme, like faith and love, is miraculous."

Servant of God Oscar Romero, martyr, ora pro nobis!

for his people who spoke about hope in the

face of what appears to be insurmountable

problems:

"Hope is not resignation; it is a commitment

to continue to struggle even when things seem

to warrant surrender, when hope flares, it

allows human beings to overcome monstrous

difficulties. It allows people to defy common

sense and confound strategists. Hope

experienced in the extreme, like faith and love, is miraculous."

Servant of God Oscar Romero, martyr, ora pro nobis!

Monday, August 15, 2011

Quote #143: nostalgia is not substitute for tradition

"A society that has made "nostalgia" a marketable commodity on the cultural exchange quickly repudiates the suggestion that life in the past was in any important way better than life today."

- Christopher Lasch (1932-1994), American social critic.

- Christopher Lasch (1932-1994), American social critic.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Quote #142: Natural law and the nature of government

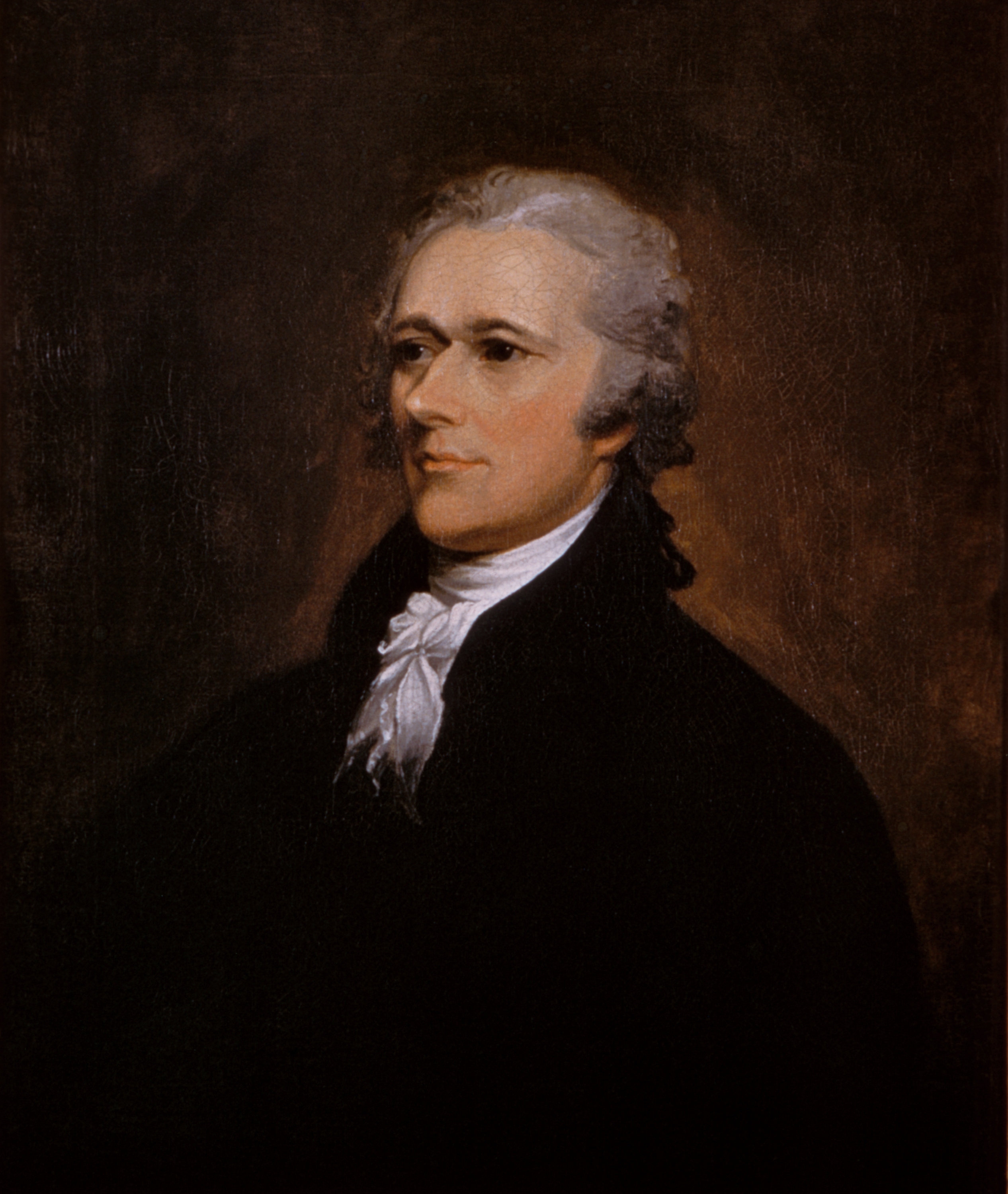

"Good and wise men, in all ages [...] have supposed that the Deity, from the relations we stand in to Himself and to each other, has constituted an eternal and immutable law, which is indispensably obligatory upon all mankind, prior to any human institution whatever.This is what is called the law of nature, “which, being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God himself, is, of course, superior in obligations to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times. No human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original.”—Blackstone.

"Good and wise men, in all ages [...] have supposed that the Deity, from the relations we stand in to Himself and to each other, has constituted an eternal and immutable law, which is indispensably obligatory upon all mankind, prior to any human institution whatever.This is what is called the law of nature, “which, being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God himself, is, of course, superior in obligations to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times. No human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original.”—Blackstone.Upon this law depend the natural rights of mankind: the Supreme Being gave existence to man, together with the means of preserving and beautifying that existence. He endowed him with rational faculties, by the help of which to discern and pursue such things as were consistent with his duty and interest; and invested him with an inviolable right to personal liberty and personal safety.

Hence, in a state of nature, no man had any moral power to deprive another of his life, limbs, property, or liberty; nor the least authority to command or exact obedience from him, except that which arose from the ties of consanguinity.

Hence, also, the origin of all civil government, justly established, must be a voluntary compact between the rulers and the ruled, and must be liable to such limitations as are necessary for the security of the absolute rights of the latter; for what original title can any man, or set of men, have to govern others, except their own consent? To usurp dominion over a people in their own despite, or to grasp at a more extensive power than they are willing to intrust, is to violate that law of nature which gives every man a right to his personal liberty, and can therefore confer no obligation to obedience.

“The principal aim of society is to protect individuals in the enjoyment of those absolute rights which were vested in them by the immutable laws of nature, but which could not be preserved in peace without that mutual assistance and intercourse which is gained by the institution of friendly and social communities. Hence it follows, that the first and primary end of human laws is to maintain and regulate these absolute rights of individuals.”—Blackstone."

- Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), American founding father, The Farmer Refuted (1775).

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Quote #141: epistle reading for the 20th Sunday in Ordinary Time

The second reading assigned in the Catholic lectionary for this Sunday is taken from St. Paul's letter to the Romans 11.13-15, 29-32. That portion of scripture reads as follows in the venerable King James Version of the New Testament:

For I speak to you Gentiles, inasmuch as I am the apostle of the Gentiles, I magnify mine office:Wise words to ponder.

If by any means I may provoke to emulation [them which are] my flesh, and might save some of them.

For if the casting away of them [be] the reconciling of the world, what [shall] the receiving [of them be], but life from the dead?

For the gifts and calling of God [are] without repentance.

For as ye in times past have not believed God, yet have now obtained mercy through their unbelief:

Even so have these also now not believed, that through your mercy they also may obtain mercy.

For God hath concluded them all in unbelief, that he might have mercy upon all.

Sunday, June 5, 2011

Quote #140: dissenting religion and the push for American Independence

From the great English statesman Edmund Burke (1729-1797) comes this analysis of the role that dissenting religion played in the American commitment to liberty at the time leading up to our Revolution:

Religion, always a principle of energy, in this new people is no way worn out or impaired; and their mode of professing it is also one main cause of this free spirit. The people are Protestants; and of that kind which is the most adverse to all implicit submission of mind and opinion. This is a persuasion not only favourable to liberty, but built upon it. I do not think, Sir, that the reason of this averseness in the dissenting churches, from all that looks like absolute government, is so much to be sought in their religious tenets, as in their history. Every one knows that the Roman Catholic religion is at least coeval with most of the governments where it prevails; that it has generally gone hand in hand with them, and received great favour and every kind of support from authority. The Church of England too was formed from her cradle under the nursing care of regular government. But the dissenting interests have sprung up in direct opposition to all the ordinary powers of the world; and could justify that opposition only on a strong claim to natural liberty. Their very existence depended on the powerful and unremitted assertion of that claim. All Protestantism, even the most cold and passive, is a sort of dissent. But the religion most prevalent in our northern colonies is a refinement on the principle of resistance; it is the dissidence of dissent, and the Protestantism of the Protestant religion. This religion, under a variety of denominations agreeing in nothing but in the communion of the spirit of liberty, is predominant in most of the northern provinces; where the Church of England, notwithstanding its legal rights, is in reality no more than a sort of private sect, not composing most probably the tenth of the people. The colonists left England when this spirit was high, and in the emigrants was the highest of all; and even that stream of foreigners, which has been constantly flowing into these colonies, has, for the greatest part, been composed of dissenters from the establishments of their several countries, and have brought with them a temper and character far from alien to that of the people with whom they mixed.- Speech on Conciliation with the Colonies, March 22, 1775.

Labels:

america,

Burke,

freedom,

god in america,

god in society,

Guarding Liberty,

religion,

republic

Thursday, June 2, 2011

Quote #139: Enduring freedom is embodied freedom

"The only freedom which can last is a freedom embodied somewhere, rooted in a history, located in space, sanctioned by a genealogy, and blessed by a religious establishment. The only equality which abstract rights, insisted upon outside the context of politics, are likely to provide is the equality of universal slavery. It is a lesson which Western man is only now beginning to learn."

- M.E. Bradford, A Better Guide Than Reason: Federalists & Anti-Federalists (Transaction Publishers: 1994), pg. xviii.

[Cross-posted at my own blog, Ordered Liberty.]

- M.E. Bradford, A Better Guide Than Reason: Federalists & Anti-Federalists (Transaction Publishers: 1994), pg. xviii.

[Cross-posted at my own blog, Ordered Liberty.]

Labels:

conservatism,

freedom,

Guarding Liberty,

Individual Rights

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Quote #138: on the duty of a Christian soldier

For it was a mark of a Christian solider to combine the greatest fortitude with the greatest attention to military discipline, and to add to nobility of mind immovable fidelity towards his prince. But, if anything dishonorable was required of him, as, for instance, to break the law of God, or to turn his sword against innocent disciples of christ, then, indeed, he refused to execute the orders, yet in such wise that he would rather retire from the army and die for his religion than oppose the public authority by means of sedition and tumult.- Pope Leo XIII, Encyclical Letter Diuturnum (On Civil Government) (1881), chapter 20.

[Cross-posted at my own blog Ordered Liberty.]

Labels:

conscience,

ethics,

god in society,

morality in society,

virtue

Monday, April 4, 2011

Quote #137: on constitutional interpretation

From one of the most influential justices in the history of the Supreme Court:

In construing the constitution of the United States, we are, in the first instance, to consider, what are its nature and objects, its scope and design, as apparent from the structure of the instrument, viewed as a whole, and also viewed in its component parts. Where its words are plain, clear, and determinate, they require no interpretation; and it should, therefore, be admitted, if at all, with great caution, and only from necessity, either to escape some absurd consequence, or to guard against some fatal evil. Where the words admit of two senses, each of which is conformable to common usage, that sense is to be adopted, which, without departing from the literal import of the words, best harmonizes with the nature and objects, the scope and design of the instrument. Where the words are unambiguous, but the provision may cover more or less ground according to the intention, which is yet subject to conjecture; or where it may include in its general terms more or less, than might seem dictated by the general design, as that may be gathered from other parts of the instrument, there is much more room for controversy; and the argument from inconvenience will probably have different influences upon different minds. Whenever such questions arise, they will probably be settled, each upon its own peculiar grounds; and whenever it is a question of power, it should be approached with infinite caution, and affirmed only upon the most persuasive reasons. In examining the constitution, the antecedent situation of the country, and its institutions, the existence and operations of the state governments, the powers and operations of the confederation, in short all the circumstances, which had a tendency to produce, or to obstruct its formation and ratification, deserve a careful attention. Much, also, may be gathered from contemporary history, and contemporary interpretation, to aid us in just conclusions

Sunday, April 3, 2011

Quote #136: On protecting our democratic republic

We should be unfaithful to ourselves if we should ever lose sight of the danger to our liberties if anything partial or extraneous should infect the purity of our free, fair, virtuous, and independent elections. If an election is to be determined by a majority of a single vote, and that can be procured by a party through artifice or corruption, the Government may be the choice of a party for its own ends, not of the nation for the national good. If that solitary suffrage can be obtained by foreign nations by flattery or menaces, by fraud or violence, by terror, intrigue, or venality, the Government may not be the choice of the American people, but of foreign nations. It may be foreign nations who govern us, and not we, the people, who govern ourselves; and candid men will acknowledge that in such cases choice would have little advantage to boast of over lot or chance.- John Adams (1735-1826), second president of the United States,

Inaugural Address (1797).

Monday, January 3, 2011

Quote #135: on virtue, happiness and the foundation of good government

"All sober inquirers after truth, ancient and modern, pagan and Christian, have declared that the happiness of man, as well as his dignity, consists in virtue. Confucius, Zo-roaster, Socrates, Mahomet, not to mention authorities really sacred, have agreed in this.

If there is a form of government, then, whose principle and foundation is virtue, will not every sober man acknowledge it better calculated to promote the general happiness than any other form?"

- John Adams (1735-1826), Thoughts on Government (April 1776).

If there is a form of government, then, whose principle and foundation is virtue, will not every sober man acknowledge it better calculated to promote the general happiness than any other form?"

- John Adams (1735-1826), Thoughts on Government (April 1776).

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

CXXXIII

"No nation can preserve its freedom in the midst of continual warfare."

-James Madison (4th President of the United States and critical member of the Constitutional Convention)

CXXXII

Quote #131: God's aid and the rise of America

"I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth -- that God Governs the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid?"

- Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Speech to the Constitutional Convention, 1787, quoted in The Essential Wisdom of the Founding Fathers, edited by Carol Kelly-Grange (Fall River Press: 2009), pg. 33.

- Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Speech to the Constitutional Convention, 1787, quoted in The Essential Wisdom of the Founding Fathers, edited by Carol Kelly-Grange (Fall River Press: 2009), pg. 33.

Labels:

Ben Franklin,

conservativism,

founders,

god in america,

god in society

Sunday, November 21, 2010

Quote #130: on the link between faith and works

"In one thing we agree that he who feareth God, and worketh righteousness shall be accepted of him and his Faith cannot be wrong whose life is in the right."

- Abigail Adams (1744-1818), American founder, Letter to Catherine Adams, April 15, 1818, quoted in The Founders on Religion: A Book of Quotations, edited by James H. Hutson (Princeton: 2005), pg. 90.

- Abigail Adams (1744-1818), American founder, Letter to Catherine Adams, April 15, 1818, quoted in The Founders on Religion: A Book of Quotations, edited by James H. Hutson (Princeton: 2005), pg. 90.

Labels:

america,

god in society,

godliness,

morality in society,

theology,

virtue

Saturday, November 13, 2010

Quote #129: the problem with the religious right

"Adherents of the new religious right reject the separation of politics and religion, but they bring no spiritual insights to politics."

- Christopher Lasch (1931-1994), American historian and social critic.

- Christopher Lasch (1931-1994), American historian and social critic.

Labels:

god in society,

good government,

morality in society

Friday, November 12, 2010

Quote #128: on the need for religion in society

"The principle of liberty and equality, if coupled with mere selfishness, will make men only devils, each trying to be independent that he may fight only for his own interest. And here is the need of religion and its power, to bring in the principle of benevolence and love to men."

- John Randolph of Roanoke (1733-1833), Congressman and leader of the National Republicans Party.

- John Randolph of Roanoke (1733-1833), Congressman and leader of the National Republicans Party.

Labels:

ethics,

god in society,

morality in society,

religion,

virtue

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Quote #127: on democracy

"As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy."

- Abraham Lincoln (1808-1865), lawyer, politician, and first Republican president of the United States.

- Abraham Lincoln (1808-1865), lawyer, politician, and first Republican president of the United States.

Labels:

Abe Lincoln,

democracy,

Guarding Liberty,

Individual Rights,

liberty

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Quote #126: on the sanctity of private property

"So great moreover is the regard of the law for private property, that it will not authorize the least violation of it; no, not even for the general good of the whole community."

- Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780), Commentary on the Laws of England.

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Quote #125: on fighting for justice

"Power never concedes anything without a demand. It never has and it never will."

- Frederick Douglass (1808-1895), former slave, African-American civil rights activist, abolitionist and American political philosopher.

- Frederick Douglass (1808-1895), former slave, African-American civil rights activist, abolitionist and American political philosopher.

Quote #124: on justice

"The precepts of the law are these: to live honestly, to injure no one, and to give every man his due. The study of law consists of two branches, law public and law private. The former relates to the welfare of the Roman State; the latter to the advantage of the individual citizen. Of private law then we may say that it is of threefold origin, being collected from the precepts of nature, from those of the law of nations, or from those of the civil law of Rome."

- Justinian (483-565), emperor of Rome, in his Institutes of Roman Law.

- Justinian (483-565), emperor of Rome, in his Institutes of Roman Law.

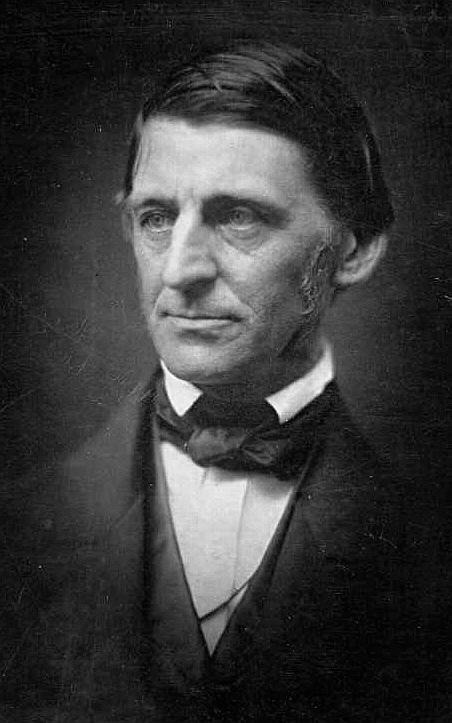

Quote #123: on virtue

"The only reward of virtue is virtue; the only way to have a friend is to be one."

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), American writer and philosopher.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), American writer and philosopher.

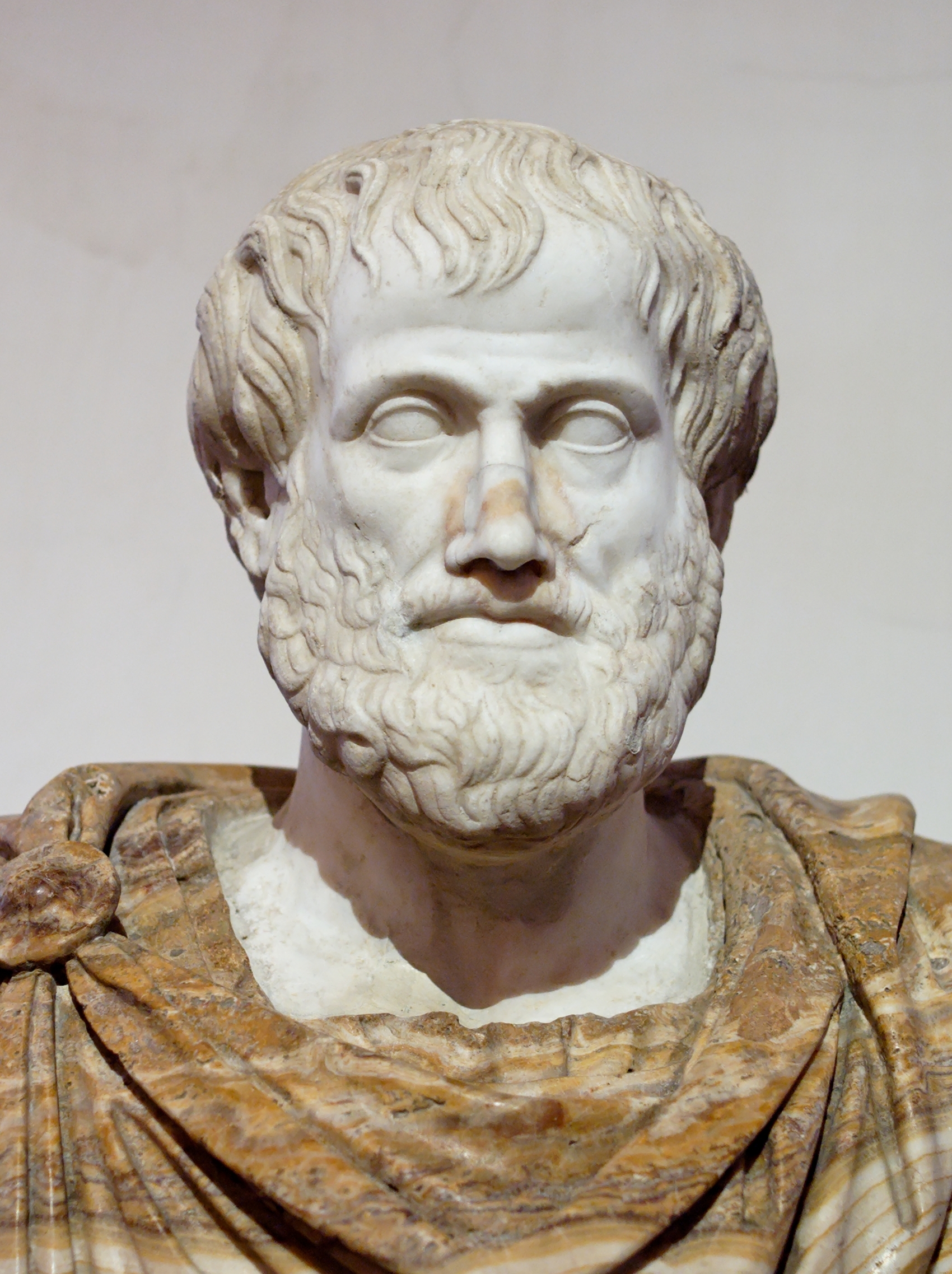

Quote #122: on ideas

"It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it."

- Aristotle (384 BC - 322 BC), ancient Greek philosopher and tutor to Alexander the Great.

- Aristotle (384 BC - 322 BC), ancient Greek philosopher and tutor to Alexander the Great.

Monday, November 8, 2010

Mother Teresa on abortion

"I always say one thing: If a mother can kill her own child, then what is left of the West to be destroyed? It is difficult to explain , but it is just that."

Mother Teresa

Monday, September 6, 2010

CXX

"Of all tyrannies a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It may be better to live under robber barons than omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron's cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end, for they do so with the approval of their own conscience."

-C. S. Lewis

Labels:

america,

big government,

c. s. lewis,

communism,

congress,

freedom,

social reform,

socialism,

tyranny

Saturday, September 4, 2010

Quote CXIX

"The truth is this: the march of Providence is so slow and our desires are so impatient; the work of progress is so immense and our means of aiding it so feeble; the life of humanity is so long and that of the individual so brief, that we often see only the ebb of the advancing wave and are thus discouraged. It is history that teaches us hope."

-General Robert E. Lee

(pictured as a young lieutenant in 1831)

Friday, September 3, 2010

Quote CXVIII

"A citizen can hardly distinguish between a tax and a fine, except that a fine is generally much lighter."

-G. K. Chesterton

Labels:

americans,

big government,

business,

capitalism,

chesterton,

congress,

economy,

taxes,

the common man

Friday, June 25, 2010

Saturday, June 5, 2010

Quote #116: on persuasion

"If you would convince a man that he does wrong, do right. But do not care to convince him. Men will believe what they see. Let them see"

- Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), American writer.

Friday, April 30, 2010

Quote #115: De Profundis by Christina Rossetti

Oh why is heaven built so far,

Oh why is earth set so remote?

I cannot reach the nearest star

That hangs afloat.

I would not care to reach the moon,

On round monotonous of change;

Yet even she repeats her tune

Beyond my range.

I never watch the scatter'd fire

Of stars or sun's far-trailing train,

But all my heart is one desire,

And all in vain:

For I am bound with fleshly bands,

Joy, beauty, lie beyond my scope;

I strain my heart, I stretch my hands,

And catch at hope.

Oh why is earth set so remote?

I cannot reach the nearest star

That hangs afloat.

I would not care to reach the moon,

On round monotonous of change;

Yet even she repeats her tune

Beyond my range.

I never watch the scatter'd fire

Of stars or sun's far-trailing train,

But all my heart is one desire,

And all in vain:

For I am bound with fleshly bands,

Joy, beauty, lie beyond my scope;

I strain my heart, I stretch my hands,

And catch at hope.

Quote #114: on excessive taxation

"Collecting more taxes than is absolutely necessary is legalized robbery." -- Calvin Coolidge, 30th president of the United States.

Labels:

big government,

coolidge,

economy,

Guarding Liberty,

liberty,

presidents,

taxes

Quote #113: on the nature of education

“Education is not the piling on of learning, information, data, facts, skills, or abilities - that's training or instruction - but is rather making visible what is hidden as a seed” -- St. Thomas More, Lord Chancellor of England and martyr.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

Why do we quote?

A good question. What is it about quotations that captivate those of us who like them? I have books of quotations -- by the Founding Fathers, by Abraham Lincoln, by various theological authors, etc. Why? What is it about the words of others that is so appealing? Partly it is authority -- the use of words by notable authors to support my own contentions. It allows me to speak without using my own voice. But that, I think, isn't the main reason. The main reason is joy in the phrasing and wisdom of others. What I like about quotations is the ability to reference a particularly well-put point or insight, and to share that literary or verbal excellence with others. That to me is why quotations are so interesting.

As Lincoln once quipped, "For those who like that kind of thing, it's the kind of thing they like."

As Lincoln once quipped, "For those who like that kind of thing, it's the kind of thing they like."

Quote #112: don't act in a hurry

"Here is a very wise rule: never act in a hurry, and always be ready to alter your preconceived ideas. And here is another principle that goes with it; don't be too ready to accept the first story that is told you, or hand on to others the rumours you hear, and the secrets entrusted to you. Find out some wise counsellor to advise you, a man of enlightened conscience, and be prepared to go by his better judgement, instead of trusting your own calculations. Believe me, a holy life gives a man the wisdom that reflects God's will, and a wide range of experience. The humbler he is, the more submissive in God's service, the more wise and calm will be his judgements on every question." - The Imitation of Christ, Bk. 1, Ch. 4, Para. 2 (Ronald Knox translation).

Saturday, April 3, 2010

Worshipping the Intellect

"There seems to be an inverse corrolary between those who worship the intellect and those who use it. [Sam] Harris, like so many atheists, is a devout worshipper of the intellect."

Mark P. Shea, Catholic blogger

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

St. Augustine (by Sandro Botticelli)

St. Ignatius Loyola (by Francisco Zurbaran)

Benjamin Rush (by Charles Willson Peale)

Patrick Henry at the Virginia House of Burgesses (by Henry Rothermel)

Edmund Burke (by Sir Joshua Reynolds)

Samuel Adams (by John Singleton Copley)

Alexander Hamilton (by John Trumbull)